Below are two images that appear to be starkly different; one in a bucolic setting, the other concrete and urban. They are in fact the same location: Stapleton Bridge at the bottom of Bell Hill, borderland between the village suburb of Stapleton on the north-eastern edge of Bristol and the grittier environs of Easton and Baptist Mill further into the cityscape.

This is a topographical snapshot through which I pass on a regular basis and one which demonstrates the complex entanglement of emotions, memories, perceptions and debate that landscape engenders. In discussing the relationship between landscape and Englishness David Matless asserts that "if landscape carries an unseemly spatiality, it also shuttles through temporal processes of history and memory. Judgements over present value work in relation to narratives of past landscape".

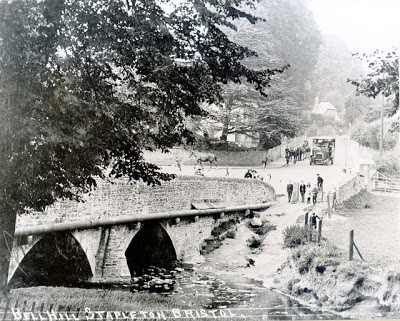

![]() The first image, a postcard photograph taken in the early twentieth century (from the Tempus Images of England: Stapleton volume) has all the elements required to conjure up feelings of wistful nostalgia for times past: the sunny black and whiteness, a ford gently sloping to a rocky river, the luxuriant trees and distant cottage. The setting populated by a group of children, a horse and a charabanc. All harmonious and timeless, everything in its right place. Never mind that such scenes were often stage-managed or that the juggernaut of suburbanisation was rapidly approaching, this is how we want Old England to be represented in our imagination; and sits well with a popular strain of elegiac gloom, tapped into by Philip Larkin in his poem Going, Going:

The first image, a postcard photograph taken in the early twentieth century (from the Tempus Images of England: Stapleton volume) has all the elements required to conjure up feelings of wistful nostalgia for times past: the sunny black and whiteness, a ford gently sloping to a rocky river, the luxuriant trees and distant cottage. The setting populated by a group of children, a horse and a charabanc. All harmonious and timeless, everything in its right place. Never mind that such scenes were often stage-managed or that the juggernaut of suburbanisation was rapidly approaching, this is how we want Old England to be represented in our imagination; and sits well with a popular strain of elegiac gloom, tapped into by Philip Larkin in his poem Going, Going:

![]() The second image, taken last summer and on my cycle route from home to work, is an equally interesting view of the same spot. But all is now changed, the only constant in the century or so between the photographs is the river Frome. The handsome arched stone bridge replaced by the straight-line utilitarianism of its 1930's successor - no doubt seen as shiny and modern at the time, but now drab and anonymous - and the ford no more. Most dramatically, the flyover carrying the M32 motorway into the heart of the city stomps over the ground-level topography like an unstoppable and disregarding lava flow of concrete; physically connected to its surroundings by its supporting pillars, but wholly dismissive of the reluctantly subterranean world cowering beneath. The bare, infertile earth in the foreground emphasising the malignant impact of this early 1970's addition; part of a wider contemporary malaise that Keith Brace articulates in his 1971 Portrait of Bristol: "I believe that Bristol is at a point of crisis in its history and that the modest-sized, relaxed, intimate city we have known is all too likely to become a disproportionately large provisional metropolis, resembling all other provisional metropolises of the future in clinical impersonality".

The second image, taken last summer and on my cycle route from home to work, is an equally interesting view of the same spot. But all is now changed, the only constant in the century or so between the photographs is the river Frome. The handsome arched stone bridge replaced by the straight-line utilitarianism of its 1930's successor - no doubt seen as shiny and modern at the time, but now drab and anonymous - and the ford no more. Most dramatically, the flyover carrying the M32 motorway into the heart of the city stomps over the ground-level topography like an unstoppable and disregarding lava flow of concrete; physically connected to its surroundings by its supporting pillars, but wholly dismissive of the reluctantly subterranean world cowering beneath. The bare, infertile earth in the foreground emphasising the malignant impact of this early 1970's addition; part of a wider contemporary malaise that Keith Brace articulates in his 1971 Portrait of Bristol: "I believe that Bristol is at a point of crisis in its history and that the modest-sized, relaxed, intimate city we have known is all too likely to become a disproportionately large provisional metropolis, resembling all other provisional metropolises of the future in clinical impersonality".

![]() But linger and look, and all is not lost. Move under the flyover and, on the right day, a sunlit vista of the neighbouring Bridge Farm opens up, framed by greenery. This eighteenth century agricultural relic (seen opposite and in the old photograph below, also taken from Images of England: Stapleton) occupies a visually stimulating juxtaposition with the modernity of the airborne motorway just metres away. A pleasing reminder that this area plays fast and loose with simplistic notions of zonal separation between urban, suburban and rural: all three rub together here. And we can begin to chip away at the, in Matthew Johnson's words, "unrestrained empiricism" of the Romantic view of landscape as a purely visual and aesthetic phenomena.

But linger and look, and all is not lost. Move under the flyover and, on the right day, a sunlit vista of the neighbouring Bridge Farm opens up, framed by greenery. This eighteenth century agricultural relic (seen opposite and in the old photograph below, also taken from Images of England: Stapleton) occupies a visually stimulating juxtaposition with the modernity of the airborne motorway just metres away. A pleasing reminder that this area plays fast and loose with simplistic notions of zonal separation between urban, suburban and rural: all three rub together here. And we can begin to chip away at the, in Matthew Johnson's words, "unrestrained empiricism" of the Romantic view of landscape as a purely visual and aesthetic phenomena.

![]() Looking in the opposite direction there is a certain grace to the curving slip road, descending along the edge of the defiant greenery of Eastville Park; a pleasing contrast of light and shade. The paved non-space below the road has become here an arena for a variety of unofficial activities: unseen daily depositors of vast amounts of bread crumbs for pigeons, a troupe engaged in fire-eating training and, most impressively, guerrilla artists decorating two of the concrete supports with bright and vibrant scenes of nature. Humanity is re-colonising this desolate void.

Looking in the opposite direction there is a certain grace to the curving slip road, descending along the edge of the defiant greenery of Eastville Park; a pleasing contrast of light and shade. The paved non-space below the road has become here an arena for a variety of unofficial activities: unseen daily depositors of vast amounts of bread crumbs for pigeons, a troupe engaged in fire-eating training and, most impressively, guerrilla artists decorating two of the concrete supports with bright and vibrant scenes of nature. Humanity is re-colonising this desolate void.

So, far from being, as it may first appear, merely a scene of brutalist alienation - an elegy for a lost land, the contemporary landscape has character and interest aplenty; a mixture of historic features, re-imagined and reused, and what Nan Fairbrother describes as the "self-contained linear landscape" of the motorway. Stepping back into the picture post card Edwardian scenes there is much that we are not told when viewing this reassuring scene, as seemingly wholesome as a period drama, that may similarly alter the initial perception.

The bridge was on the edge of eighteenth century Kingswood Chase, a remnant of the much larger Royal Forest of Kingswood that covered 200 square miles until disafforestation in 1228. By the eighteenth century, and continuing into the nineteenth, Kingswood was viewed as a hot-bed of criminality, non-conformity, popular protest and general unruliness, with a rapidly growing population of colliers, quarrymen and other squatter-inhabitants. John Wesley sums up the areas reputation succinctly: "Few persons have lived long in the West of England who have not heard of the colliers of Kingswood: a people famous from the beginning hitherto, for neither fearing God nor regarding man". By the time of the black and white photographs shown here much of Kingswood and the areas surrounding Stapleton had become heavily populated and industrialised and Eastville Park, bounded by the bridge, had been established as a municipal green lung for the urban population. As it has largely remained, the area was already an oasis of residual or revenant rurality, surrounded by 'Ouses, Ouses, Ouses'. The chimera of old world stability and orderliness is further undermined by a decidedly non-photogenic landmark a mile down the road. At the opposite end of the village stood (and still stands) a huge Victorian complex that had seen time as a prison for 5,000 French soldiers during the Napoleonic wars, a lunatic asylum and workhouse for the poor.

Cycling home over the bridge and under the flyover I feel the full force of these diverse and conflicting temporal and spatial energies; a flash mob of liminal stimuli skulking in the shadows. Landscape as multi-sensory immersion. I sigh heavily at the imagined memory of the old house, 'Sunnybanks', (though I have never seen it) that used to stand on the higher ground above the bridge and was demolished to make way for the motorway embankment. But I also can't help finding the fleeting phenomenological experience of under-passing the concrete monolith exhilarating; sound-tracked by the disembodied harsh monotone of the traffic above, like a minimalist symphony of repetitive drones. And the prospect of the last mile home along the still green banks of the Frome, with the potential for sightings of heron, kingfisher or barn owl, spurs on my tired limbs and lifts the landscapist spirit further.

References

Avon Archaeological Council and Avon Local History Association, 1982 Avon Past 7 Pamphlet.

Baker, Kenneth (Ed.), 2000 The Faber Book of Landscape Poetry London: Faber and Faber.

Bartlett, John, 2004 Images of England: Fishponds Stroud: Tempus.

Brace, Keith, 1971 Images of Bristol London: Robert Hale.

Fairbrother, Nan, 1972 New Lives, New Landscapes London: Penguin.

Johnson, Matthew, 2007 Ideas of Landscape Oxford: Blackwell.

Matless, David, 1998 Landscape and Englishness London: Reaktion.

Smith, Veronica, 2004 Images of England: Stapleton Stroud: Tempus.

Wylie, John, 2007 Landscape Oxford: Routledge.

This is a topographical snapshot through which I pass on a regular basis and one which demonstrates the complex entanglement of emotions, memories, perceptions and debate that landscape engenders. In discussing the relationship between landscape and Englishness David Matless asserts that "if landscape carries an unseemly spatiality, it also shuttles through temporal processes of history and memory. Judgements over present value work in relation to narratives of past landscape".

The first image, a postcard photograph taken in the early twentieth century (from the Tempus Images of England: Stapleton volume) has all the elements required to conjure up feelings of wistful nostalgia for times past: the sunny black and whiteness, a ford gently sloping to a rocky river, the luxuriant trees and distant cottage. The setting populated by a group of children, a horse and a charabanc. All harmonious and timeless, everything in its right place. Never mind that such scenes were often stage-managed or that the juggernaut of suburbanisation was rapidly approaching, this is how we want Old England to be represented in our imagination; and sits well with a popular strain of elegiac gloom, tapped into by Philip Larkin in his poem Going, Going:

The first image, a postcard photograph taken in the early twentieth century (from the Tempus Images of England: Stapleton volume) has all the elements required to conjure up feelings of wistful nostalgia for times past: the sunny black and whiteness, a ford gently sloping to a rocky river, the luxuriant trees and distant cottage. The setting populated by a group of children, a horse and a charabanc. All harmonious and timeless, everything in its right place. Never mind that such scenes were often stage-managed or that the juggernaut of suburbanisation was rapidly approaching, this is how we want Old England to be represented in our imagination; and sits well with a popular strain of elegiac gloom, tapped into by Philip Larkin in his poem Going, Going: "And that will be England gone,

The shadows, the meadows, the lanes,

The guildhalls, the carved choirs.

There'll be books; it will linger on

In galleries; but all that remains

For us will be concrete and tyres."

.jpg) The second image, taken last summer and on my cycle route from home to work, is an equally interesting view of the same spot. But all is now changed, the only constant in the century or so between the photographs is the river Frome. The handsome arched stone bridge replaced by the straight-line utilitarianism of its 1930's successor - no doubt seen as shiny and modern at the time, but now drab and anonymous - and the ford no more. Most dramatically, the flyover carrying the M32 motorway into the heart of the city stomps over the ground-level topography like an unstoppable and disregarding lava flow of concrete; physically connected to its surroundings by its supporting pillars, but wholly dismissive of the reluctantly subterranean world cowering beneath. The bare, infertile earth in the foreground emphasising the malignant impact of this early 1970's addition; part of a wider contemporary malaise that Keith Brace articulates in his 1971 Portrait of Bristol: "I believe that Bristol is at a point of crisis in its history and that the modest-sized, relaxed, intimate city we have known is all too likely to become a disproportionately large provisional metropolis, resembling all other provisional metropolises of the future in clinical impersonality".

The second image, taken last summer and on my cycle route from home to work, is an equally interesting view of the same spot. But all is now changed, the only constant in the century or so between the photographs is the river Frome. The handsome arched stone bridge replaced by the straight-line utilitarianism of its 1930's successor - no doubt seen as shiny and modern at the time, but now drab and anonymous - and the ford no more. Most dramatically, the flyover carrying the M32 motorway into the heart of the city stomps over the ground-level topography like an unstoppable and disregarding lava flow of concrete; physically connected to its surroundings by its supporting pillars, but wholly dismissive of the reluctantly subterranean world cowering beneath. The bare, infertile earth in the foreground emphasising the malignant impact of this early 1970's addition; part of a wider contemporary malaise that Keith Brace articulates in his 1971 Portrait of Bristol: "I believe that Bristol is at a point of crisis in its history and that the modest-sized, relaxed, intimate city we have known is all too likely to become a disproportionately large provisional metropolis, resembling all other provisional metropolises of the future in clinical impersonality". Undeniably this kind of motor-city infrastructure, conceived on a drawing-board - the product of a late twentieth-century narrowly focused technocratic imagination - unsettles the balance of the existing landscape through which it courses. The benefits that it provides - harder, faster, stronger communications links between city and hinterland - are disputable and, in any case, locally irrelevant compared to what it takes away not only in terms of pollution but also aesthetically and spiritually.

.jpg) But linger and look, and all is not lost. Move under the flyover and, on the right day, a sunlit vista of the neighbouring Bridge Farm opens up, framed by greenery. This eighteenth century agricultural relic (seen opposite and in the old photograph below, also taken from Images of England: Stapleton) occupies a visually stimulating juxtaposition with the modernity of the airborne motorway just metres away. A pleasing reminder that this area plays fast and loose with simplistic notions of zonal separation between urban, suburban and rural: all three rub together here. And we can begin to chip away at the, in Matthew Johnson's words, "unrestrained empiricism" of the Romantic view of landscape as a purely visual and aesthetic phenomena.

But linger and look, and all is not lost. Move under the flyover and, on the right day, a sunlit vista of the neighbouring Bridge Farm opens up, framed by greenery. This eighteenth century agricultural relic (seen opposite and in the old photograph below, also taken from Images of England: Stapleton) occupies a visually stimulating juxtaposition with the modernity of the airborne motorway just metres away. A pleasing reminder that this area plays fast and loose with simplistic notions of zonal separation between urban, suburban and rural: all three rub together here. And we can begin to chip away at the, in Matthew Johnson's words, "unrestrained empiricism" of the Romantic view of landscape as a purely visual and aesthetic phenomena.  Looking in the opposite direction there is a certain grace to the curving slip road, descending along the edge of the defiant greenery of Eastville Park; a pleasing contrast of light and shade. The paved non-space below the road has become here an arena for a variety of unofficial activities: unseen daily depositors of vast amounts of bread crumbs for pigeons, a troupe engaged in fire-eating training and, most impressively, guerrilla artists decorating two of the concrete supports with bright and vibrant scenes of nature. Humanity is re-colonising this desolate void.

Looking in the opposite direction there is a certain grace to the curving slip road, descending along the edge of the defiant greenery of Eastville Park; a pleasing contrast of light and shade. The paved non-space below the road has become here an arena for a variety of unofficial activities: unseen daily depositors of vast amounts of bread crumbs for pigeons, a troupe engaged in fire-eating training and, most impressively, guerrilla artists decorating two of the concrete supports with bright and vibrant scenes of nature. Humanity is re-colonising this desolate void. The bridge was on the edge of eighteenth century Kingswood Chase, a remnant of the much larger Royal Forest of Kingswood that covered 200 square miles until disafforestation in 1228. By the eighteenth century, and continuing into the nineteenth, Kingswood was viewed as a hot-bed of criminality, non-conformity, popular protest and general unruliness, with a rapidly growing population of colliers, quarrymen and other squatter-inhabitants. John Wesley sums up the areas reputation succinctly: "Few persons have lived long in the West of England who have not heard of the colliers of Kingswood: a people famous from the beginning hitherto, for neither fearing God nor regarding man". By the time of the black and white photographs shown here much of Kingswood and the areas surrounding Stapleton had become heavily populated and industrialised and Eastville Park, bounded by the bridge, had been established as a municipal green lung for the urban population. As it has largely remained, the area was already an oasis of residual or revenant rurality, surrounded by 'Ouses, Ouses, Ouses'. The chimera of old world stability and orderliness is further undermined by a decidedly non-photogenic landmark a mile down the road. At the opposite end of the village stood (and still stands) a huge Victorian complex that had seen time as a prison for 5,000 French soldiers during the Napoleonic wars, a lunatic asylum and workhouse for the poor.

Cycling home over the bridge and under the flyover I feel the full force of these diverse and conflicting temporal and spatial energies; a flash mob of liminal stimuli skulking in the shadows. Landscape as multi-sensory immersion. I sigh heavily at the imagined memory of the old house, 'Sunnybanks', (though I have never seen it) that used to stand on the higher ground above the bridge and was demolished to make way for the motorway embankment. But I also can't help finding the fleeting phenomenological experience of under-passing the concrete monolith exhilarating; sound-tracked by the disembodied harsh monotone of the traffic above, like a minimalist symphony of repetitive drones. And the prospect of the last mile home along the still green banks of the Frome, with the potential for sightings of heron, kingfisher or barn owl, spurs on my tired limbs and lifts the landscapist spirit further.

References

Avon Archaeological Council and Avon Local History Association, 1982 Avon Past 7 Pamphlet.

Baker, Kenneth (Ed.), 2000 The Faber Book of Landscape Poetry London: Faber and Faber.

Bartlett, John, 2004 Images of England: Fishponds Stroud: Tempus.

Brace, Keith, 1971 Images of Bristol London: Robert Hale.

Fairbrother, Nan, 1972 New Lives, New Landscapes London: Penguin.

Johnson, Matthew, 2007 Ideas of Landscape Oxford: Blackwell.

Matless, David, 1998 Landscape and Englishness London: Reaktion.

Smith, Veronica, 2004 Images of England: Stapleton Stroud: Tempus.

Wylie, John, 2007 Landscape Oxford: Routledge.